1900 UP TO THE INDEPENDENCE OF INDIA

This section deals with the second fifty years of the life of the College (1895-1945) and roughly corresponds to the time scale of the turn of the century (1900) to the Independence of India (1947).

At the turn of the century, the demographics of the College was influenced by four major factors:

- The academic accreditation available for pupils in the education sector as the sector became more formalised.

- The rigid policy of segregation of races, despite the movements for change.

- The angst surrounding the privileges for the European and, now increasingly, the Anglo-Indian community in India, in the face of general competition and merit.

- The Independence of India and its effect on demographics of the College.

INFLUENCE OF ACADEMIC ACCREDITATION ON DEMOGRAPHICS

In the Principal’s Report of 1897, the Principal spelled out the culmination of the school leaving system and the evaluation available at that that time. “The more important public examinations for which we compete are five in number: namely those for the Roorkee College Engineering Department; the Upper Subordinate Civil English Department; the Government High or Final Standard for European Schools; the Middle Standard; and the Primary School.”

He went on to describe the challenges and opportunities associated with the school-leaving examinations:

“The highest of these is the Roorkee Engineer Entrance Examination … It seems a matter of some moment that so few of the successful candidates for this, one of the best avenues for employment in India, should be from the European community. … We would suggest that it would be of advantage to extend the area of competition by removing one or two of the present restrictive regulations. Especially the one placed first in the Government rules stating that ‘candidates for admission to the Engineering Class must be statutory Natives of India’. … At the present time owing to financial pressure there are many European parents in this country who are unable to send their children to England; parents who have spent the best part of their lives in India, but who are not, and cannot declare themselves to be, statutory Natives of India.”

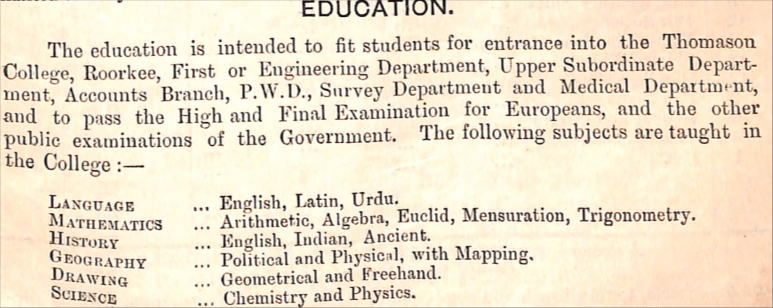

At the end of the 19th century the objectives of the School were spelled out in the Prospectus of 1899:

At the Annual Prize Distribution on 10 April, 1900, Principal Gaskell-Sykes dispensed with the reading of a formal report, to use the opportunity to address parents on the curriculum required at La Martiniere College. Speaking on the significance of a general education rather than a purely technical one, he said:

“One of these questions (of the day) has reference to the place which Technical or Industrial education should occupy in schools like the Martiniere. Our own opinion is that beyond an ordinary carpenter’s workshop and a draughtman’s room, little should be attempted in this direction in a school, the main object of which is literary education associated as a matter of course with physical training in various ways. … Students should come to a course of Technical Education thoroughly prepared by a sound Elementary Education and with a mental training and discipline which can be obtained only from a secondary education of a general and not a special character…”

Principal Gaskell-Sykes was clear that only the most gifted would be eligible for the top posts. The Martiniere, it was evident, prepared those who persevere for respectable subordinate posts:

“Another of the questions of the day in this country has reference to openings for a start in life for young men on leaving school… For those who persevere and prepare themselves at school there are many openings inviting competition. For those in the school for instance who are not likely to reach the highest classes there are subordinate posts in the Telegraph Departments, the Post Office, the Forests, Railways, the Salt and Opium Departments the Subordinate Medical Service, the Subordinate Department of Public Works, besides posts of various kinds in printing establishments and in manufacturing and mercantile pursuits. For the more gifted boys there are Accounts and Finance Departments, the Survey of India, and the Engineering Branch of the Public Works Department. Though some of the Martiniere boys have at various times passed into the Army through Sandhurst or Woolwich, and others into the Indian and Army Medical Services through examinations in England, we are not at present referring to these but confining our attention to openings that present themselves directly and immediately in this country.

“… If the Europeans and domiciled in this country do not exert themselves and establish their superior claims by shewing themselves the best qualified in these competitions they will have no one to blame but themselves if these good things go, as indeed they are already going to a very great extent, to the natives of this country.”

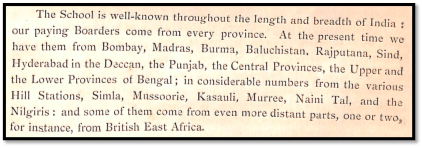

At the turn of the century, the demographics of the College displayed representation from all parts of British India, a fact proudly presented by the Principal in his Annual Report, 1901:

The protective nurturing of the Girls’ establishment came to an end in 1908 when the Girls; establishment was designated as La Martiniere Girls’ School, later to be La Martiniere Girls’ College. The overall numbers were immediately reduced, and the College reverted to being an all-boys’ institution. The demographics had changed, yet again. The formal conclusion to this phase in the demographic history of the College concluded when all formal documents were handed over to the Girls’ School, drawing a double line to end this chapter. Principal Gaskel-Sykes Governors recorded the final resolution on 1 September 1908 ordering that a copy of the recorded proceedings related to the Girls’ establishment for the previous five years be handed over to the Secretary of the Girls’ School.

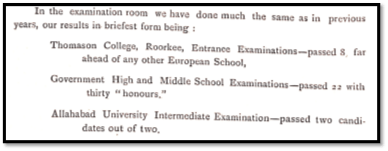

On the academic front, the School-leaving examinations continued to be qualifying examinations for entrance to Thomason College, Roorkee, the Government High and Middle School Examinations and by 1913, the Allahabad University Intermediate Examinations, which would, in 1921 become the autonomous Intermediate Board.

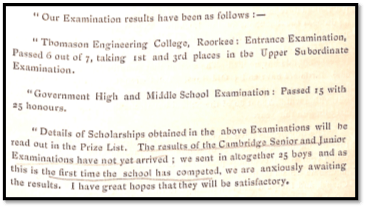

By 1914, Principal Garnett proudly announced affiliation of the College for the Cambridge University examinations:

In May 1916, Lt Col Sir Louis Stuart, CIE prepared a Note on the General Administration and Financial Position of La Martiniere College, Lucknow. He was later the Judicial Commissioner of Lucknow and Chairman of the Local Committee of Governors. Lt Col Sir Stuart presented a detailed analysis of the contemporary demographics of the College and suggested what was required for the rehauling of the College in academics and finance:

“From the time of the Mutiny (I need not go back further) to 1871 when Mr Sykes took charge the task of the Governors was comparatively easy. During that period, the Anglo-Indian of the class that came to the Martiniere had the best opportunities of obtaining remunerative employment that he has probably ever had in British India. The Mutiny had reduced the number of available candidates, and the events after the Mutiny had increased the number of posts. Further, there were very few other schools in this part of India. The present class of Hill schools had hardly come into existence, and the Martiniere was a good a place for education as could be found in the country.

“From 1871 to 1909 when Mr Sykes retired, conditions got more difficult, but the position of the Martiniere still remained good… Mr Sykes laid himself out to convert the Martiniere into the cramming establishment for Rurki. … What was the consequence? Parents sent their sons to the Martiniere in preference even to good Hill schools and the number of Boarders was as great as could be accommodated…

“When Sir Harcourt Butler came to Lucknow as Deputy Commissioner and as such became ex-officio Governor of the Martiniere he was not satisfied either with Mr Sykes or with the Martiniere methods. He found the School slipshod and slovenly. … Then came Mr T. P. Wood who was Principal till 1915. Mr T. P. Wood got in several new members on the staff and tried hard to turn the school into something like an English Public School. But the result has so far not been very gratifying. As an Establishment for providing a career for Anglo-Indian boys the School is not what it used to be. (Mr Sykes) had this great advantage that he understood the pupils and the parents of the pupils, and the pupils and the parents understood him. His methods may not appeal to the father of an English Public-School boy but they appealed to the father of the Martiniere boy. We must remember that the parents of the Martiniere boy think very little of refinement, cultivation of the humanities, formation of character and so on. They want a career for their sons as cheap as possible. In Mr Sykes’ time they got it.”

In keeping with the times, the Inspector of Schools recommended that the College be upgraded to an Intermediate College for Anglo-Indians. A decision in this regard was taken on 23 April 1922:

“IV The Inspector of European Schools report on his annual inspection was laid on the table. In the last paragraph he recommends that the Trustees or those responsible should inaugurate reforms in the Institution bringing it more into line with an Intermediate College for Anglo-Indians.

This point was discussed, and it was resolved that the Trustees of the College be invited to meet the Governors of the College in the cold weather of 1922 to discuss the question of finance and the status of the College and its alumni.”

In the Principal’s Report presented in 1923, Principal R. S. Weir announced that the College had been recognised by the Intermediate Board and that the first batch would be sent up in 1924 year.

There were wider options open at the close of the first quarter of the century, for a more general education to be available. Naturally, this also brought on a greater pressure for admission into the College which was circumscribed by restrictive numbers and percentages for racial representation. In 1924, the Principal for perhaps the first time in the history of the College admitted to the redundancy of the Roorkee engineering entrance examinations for which the College had been converted into a veritable ‘cramming class’:

“The Roorkee College examination which some years ago bulked so largely in the College life has almost ceased to affect us. Owing to the rise of colleges all through the Province it is now waste of time to attempt to enter Roorkee until one has passed at least the intermediate examination. For this reason, the Governors of the College obtained recognition from the Intermediate Board and last year we sent up our first crop of three boys from class XII of whom one obtained a scholarship. We are presenting for the intermediate this year no fewer than 9 boys and have lively hopes of their success.”

La Martiniere was progressively being compelled to align with the educational systems and changes advised for British Schools in India. This included following the recommendations of the Committee on Anglo-Indian Education, more popularly known as the Barne’s Report (1946). In conjunction with the Sargent Scheme (1944) for literacy in post-Independent India, the College would have to align itself with the trends recommended, rather than an earlier rejection of the Hartog Commission report (1929) that had been critical of the elitist systems of European Schools in India.

Leave a comment