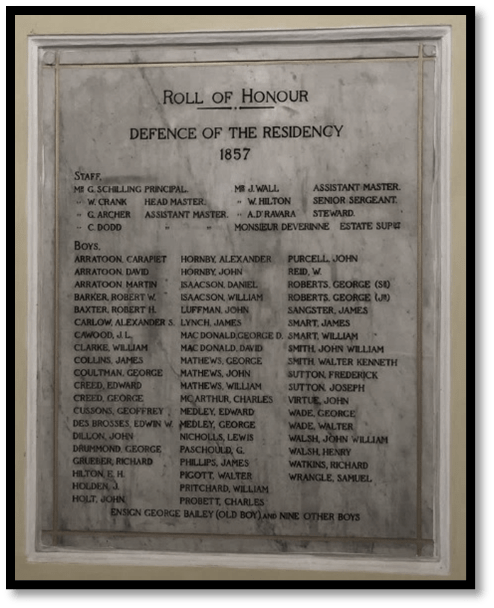

Within 12 years of the nascent institution being established, the cataclysmic events of 1857 took place. Even prior to the hostilities the Native school was disbanded with the pupils and the teachers running away. In well-documented narratives, the European and Anglo-Indian boys were ordered to move to the Residency. When the siege was lifted in November, 1857 the boys were relocated to Benares where they remained till 1859.

The catastrophic events of May, 1857 and the involvement of the Martiniere boys thereof are well-recorded in history. Understandably, the Local Committee of Governors did not meet during this time. The last decision, in circulation, by the Committee before the outbreak was to admit two boys – George Campbell and George Creed to the Foundation. This was on 2 May, 1857. Campbell is not recorded as being among the boys evacuated to the Residency. George Creed’s name does appear.

Within the confines of the Residency and under siege, the boys, with proverbial British stiff upper-lip resilience, continued to receive limited instruction. Principal George Schilling in his annual report of 1858 records:

School books sufficient to carry on the studies of the Christian pupils, with their summer clothing were taken in, as much in fact as coolies could be obtained to carry. For a few days, that is from the 18th to the 30th of June the servants of the Establishment continued to work, but their desertion on the disastrous day of Chinhut, left only a baker, hired to bake on the Gaol System a few days previously and a Masalchi to do whole work of the Establishment.

(VII) Arrangements had in consequence to be made for all domestic work to be carried on by the boys, and for the first time regular school-work was stopped. Some boys were told off to attend upon the sick, some few to attend upon sick officers, whose servants had left them, some to sweep the compounds every morning and draw water, some to grind the daily rations of corn, and some to cook the boys’ meals. Keeping watch two hours at dusk until the Masters came on duty, and digging wells for the filth of the Establishment was the especial duty of the bigger boys. Washing their own clothes was the daily duty of all but the very little ones.

“In addition to the work, above mentioned, the Boys with a few others belonging to the Garrison, for one week, instead of attending upon the sick at the Hospital, ground corn for the general supply. The work was however not done satisfactorily, as the boys had not strength for it, though they did their utmost, and a few of the big boys also assisted in working the Telegraph on the residency House communicating with the Allum Bagh.”

(XVI) The Boys arrived at Benares on the 15th of January which allowed time to make some preparations for their comfort and also for a Feast given instead of that which had unavoidably been omitted on Founder’s day. Sufficient supplies of clothing, furniture and other necessaries have been obtained, though with some difficulty, in consequence of the war, and the School is at the present date well settled, and the School is at the present date well settled, and the classes are being carried on regularly according to the accompanying routines (Appendix 1, 2). Though the boys have lost in actual knowledge during the months that they have been without school work, they appear to have gained in intelligence by what they have gone through and they are also more self-reliant and show a more kindly feeling towards each other than before.

The College moved back to Lucknow by bullock train, in March, 1859 under the efficient management of Captain J. Cockerell, who had been serving as the Secretary to the Committee in the absence of Mr Schilling.

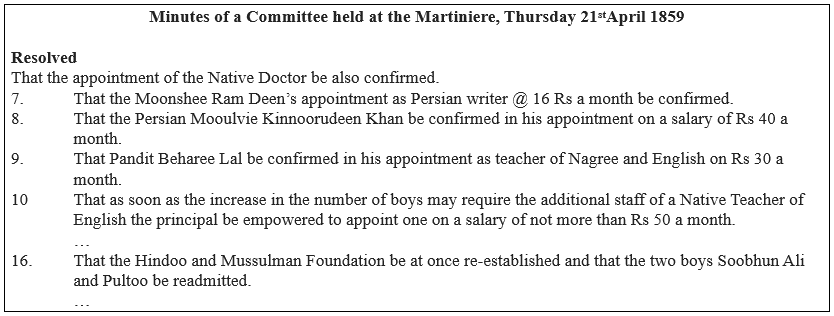

Fear and suspicion of the native populace gripped those at La Martiniere. The Native Department did not reassemble in Constantia immediately. The Native School had to be re-established as its existence was an integral part of the Scheme of Administration demanding that pupils from all communities be admitted to the College. Fresh appointments had to be made in the place of those teachers who did not return after the Uprising:

THE FIRST BOARDERS

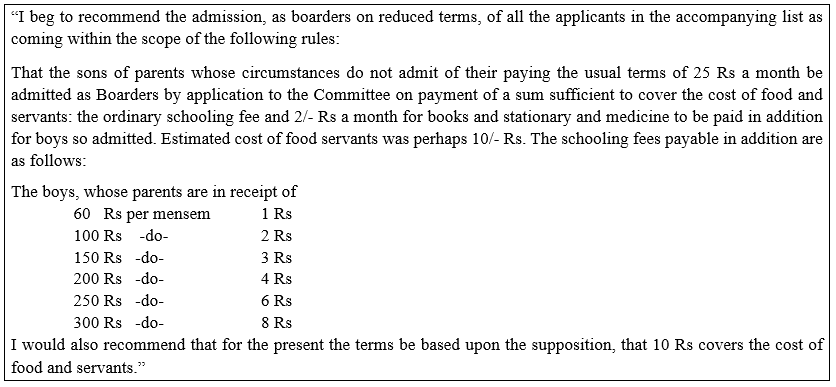

Upon the return of the School to Lucknow, it was found necessary to admit Boarders, to supplement income, especially following the renovation required because of the destruction during the Uprising. Principal, Mr George Schilling on 17 May, 1859 wrote to the Governors:

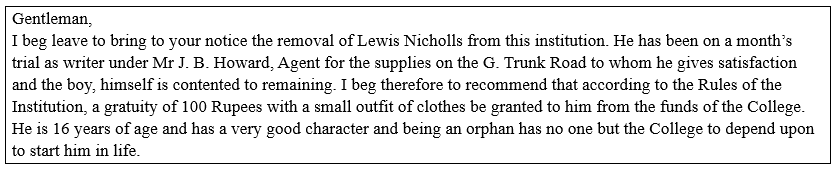

GRATUITY

Some of the boys who had been in the School shortly after its establishment were now young men, ready to go out into the world. While the school was still in Benares in October, 1858, the Capt. Cockrell, the Hony Secretary, acting in place of Mr Schilling recommended to the Committee for a gratuity to be granted to a senior boy who had been recently employed.

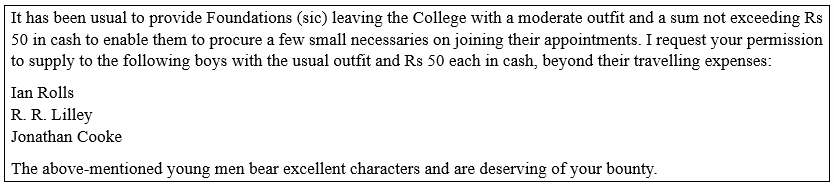

Ten years later, by January, 1869, the recommendation was altered to provide clothes and a small purse.

In the meantime, community affiliation was becoming more marked. The number of boys who could be accommodated on the European and Anglo-Indian Foundation was increased. At a meeting of the Committee on 7 November, 1859, it was resolved that “the number of wards on the European Christian Foundation be raised from 70 to 100; and that the number in the Native Foundation be increased to 45; 15 to be Hindus, 15 to be Mussulmen, and 15 Christians”.

MILITARY COMPORTMENT

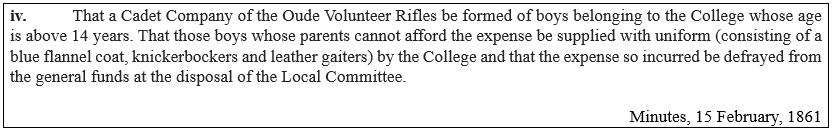

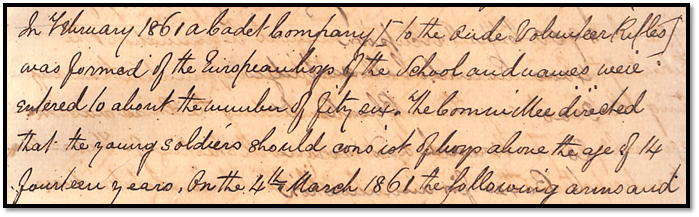

Following the harrowing events of 1857, the first formalisation of what was already a strong military tradition was the establishment of the Cadet Company of the Oude Volunteer Rifles. The Volunteer Force was a citizen army created as a popular movement throughout the British Empire in 1859. Many of the regiments of the present Indian Army are directly descended from Volunteer Force units. In 1860 the Cadet Corps was formed, consisting of school-age boys. La Martiniere was immediately affiliated. Like the adult volunteers, the boys were supplied with arms by the War Office. Cadet Corps were usually associated with private schools. They paraded regularly in public.

This not only increased the military discipline for a residential school but also trained the boys for defence in volatile times, where a few years earlier there had been an unexpected call to arms. The gap between the European ‘Us’ and the native ‘Them’ was starkly increasing. The bearing of arms and military drill inspired generations to join the armed forces both for Empire and later, independent India. The excellence in activities related to the National Cadet Corps (NCC) thereafter is a direct offspring of this exercise.

This was duly reported in the Annual Report, along the extensive list of arms and ammunition that had been supplied to the College.

A VERY ENGLISH SCHOOL

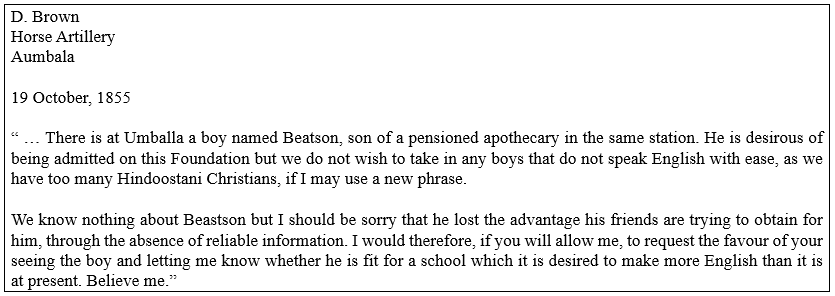

Great emphasis was being laid on pupils’ ability to communicate in English, for boys on the European Foundation. This was despite Claude Martin’s diktat for the school to be established “to learn the English language”. Boys were refused admission if they were deficient in English language skills, even though this was the raison d’etre for the school’s existence.

Comparisons were made with Eton and Winchester. In fact, it was seen as a matter of pride, that more children, were looked after by the Martin Foundation than, at Winchester itself. There were constant attempts for the school to be made more European. This extended to the decision that children above the age of 8 years would only be admitted College if they knew the English language.

Principal Leonidas Clint in 1855 wrote in despair regarding the credentials of a boy who had the most European appearance but who had to be dealt with like a native.

A similar complaint was made regarding the standard of English in the College by Principal Stobart in the Principal’s Report of 1861:

If indeed the standard for the admission of pupils could be raised, if that which is called the European Foundation of the College were really so , if instead of boys who differ little in their first joing the College from natives we could have English boys to a greater extend then – with the difficultles above alluded to removed.

On 12 May, 1865, the Governors reiterated “applicants for their children to the Foundation be told that they must take steps to have the children taught English. When the children can speak English and have fair English manners and habits, applications for their admission will be entertained.”

RACIAL SEGREGATION

In 1871, a reference was made to a letter from Mr Charles Currie, the Commissioner of Lucknow and Governor of the College, regarding the admission of a little Abyssinian boy to the Foundation of the College (European Department). It was directed that answer was to be sent “that there are at the present no vacancies, that the list of the applicants is full and that there is no prospect of the boy being taken”.

Racial segregation was a reality. In 1877, for example, two boys whose parents had applied for Free Foundation were denied the privilege, the Governors resolving: “Of the candidates in List B Henry L******d (VIII) and Robert L******d (IX) being ‘natives with European names’ are ineligible and their names are to be removed from the list”.

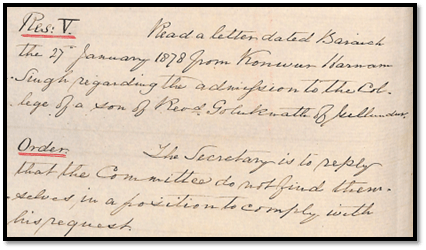

Being Christian in faith did not warrant admission. In March 1898, the Committee considered a letter from Kunwar Harnam Singh, seeking admission for the son a Christian Reverend Goluknath of Jalandhar. The Order of the Committee was terse:

The ‘No-Native’ policy, extended to all Non-European communities in subtle and not so subtle refusals for admission of boys over the years. In April 1879, Mr Eduljee, a Parsee gentleman residing in Lucknow applied for admission of his two sons as paying day-scholars. By Order of the Committee, “… the Principal (was) directed to reply that according to the Rules of the College the application cannot be entertained.” Mr Eduljee then met the Principal in his office on 21 October 1879 and followed up the meeting with another application for admission of the boys as paying day-scholars. The Committee remained adamant and the Principal was directed “to refer the previous resolution of 2 April, 1879 to the applicant, a copy of which had been sent to him.”

FEE STRUCTURE

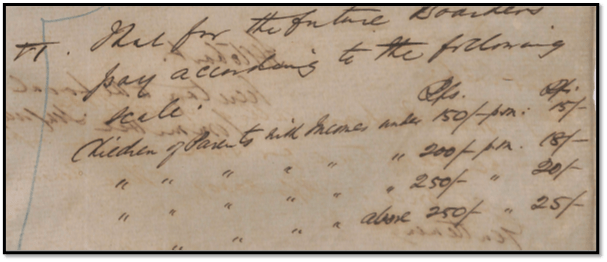

On 12 October, 1863, a revised fees structure was announced for Boarders and Days-scholars. As before, this was based on a sliding scale, depending on the income of the parent:

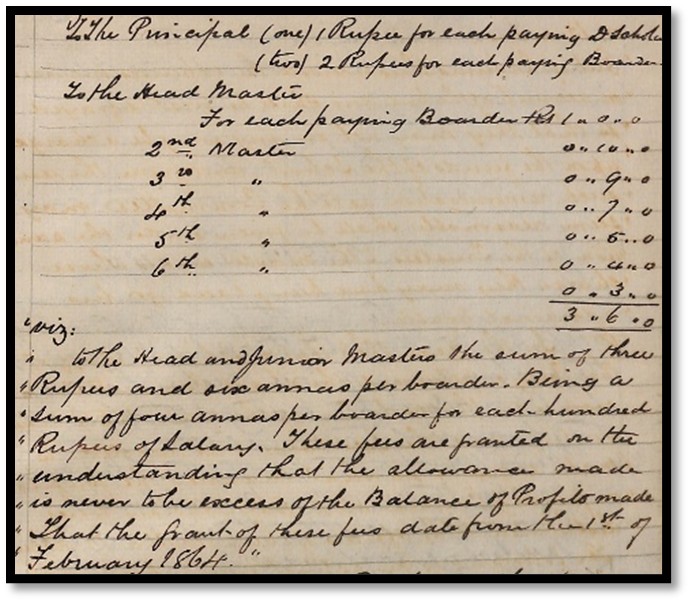

CAPITATION FEES

In 1864, rules allowing capitation fees payable were passed. This was an unofficial donation, collected by the College in exchange for a boy’s admission.

The allowances were made on the understanding that they were never to be in excess of the balance of profits on boarders’ payments. This condition was later overlooked. The benefits were distributed among the Academic Staff in a well-documented commercial exercise. This was bound to affect the demography of the Institution, as admission now had a commercial interest.

LOCAL GUARDIAN, AGENT AND CAUTION MONEY

The formal structure for care and responsibility of resident scholars now also included representatives of the pupil’s family. In January, 1867 it was resolved:

“That in the case of the admission of paying boarders and day-scholars who may in future be admitted to the College and whose parents reside out of Lucknow, be expected to appoint an Agent in Lucknow for the payment of the College fees. This rule is similar to one in force in the Calcutta Martiniere. Also, that in the case of boarders that applicants furnish the name of some respected person who will undertake to receive the boys in case of the death of their parents.”

By the end of the year, this rule was tweaked to predict the introduction of a Caution Money clause, by parents of Boarders being expected to deposit two months fees in case an Agent or Guardian could not be appointed.

THE LAWRENCE REPORT

A major furore was created in the College in 1874 with the publication of what came to be known as the Lawrence Report. Mr A. Lawrence had conducted a study of European and Eurasian Schools in India. The twelve suggestions regarding the College, on Page 213 of this report, were considered offensive by the Local Committee of Governors. It also led to definite policy statements being formulated regarding the demographics of La Martiniere College, Lucknow. It led to serious re-examination of the character of the College and determined its course for the future.

The chief suggestions in the Lawrence Report that were found offensive to the Committee were recorded with explanations by each member of the Committee on 14 August, 1874:

Suggestion III “The Martiniere should become a portion of the educational system of the Country.”

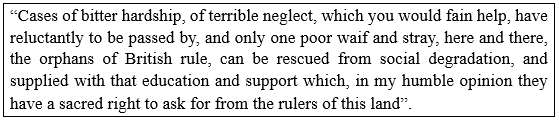

The seemingly innocuous language had ramifications that were objected to by every Member. In essence, it was felt that the ethos of the Institution, was sought to be dramatically modified. Rev. Moore, a Member of the Committee who had served as Chaplain of Benares when the College was temporarily lodged there in 1858-59, objected vehemently, writing that the attempt would: “make the Martiniere such, viz. a refuge for bastards and thieves and bazaar sweepings … In a word the Martiniere is to become a portion of the educational system of the country by taking the lowest seat until another prophet arises to send us up higher again.”

Principal Stobart spelled out the charitable principle on which the College had developed until then, with regard to children specially chosen for assistance by the Founder: “My own views are that these European and Eurasian children ought to be humanely treated, treated with respect and with reverence: that all means should be taken to raise them in the social scale, to give them self-respect, to make them truthful and honest and brave, and that everything that savours of ‘pauperism’.”

Suggestion IV “That it should be made a great cheap School or Asylum for poor children, Orphans having the preference.”

Mr J. C. Nesfied, co-opted to the Committee as the Director of Public Education, Oudh and more famously known for his authoritative book on English Grammar was of the opinion “that a school which is organized and worked on the principles of an Asylum, Refuge, or Workhouse, and which sets up an educational barrier and refuses to educate beyond it at any price, can never afford a wholesome training to the young.”

In a rare development, the Committee resolved that their Opinions be published in a printed format and circulated.

THE FIRST PROSPECTUS

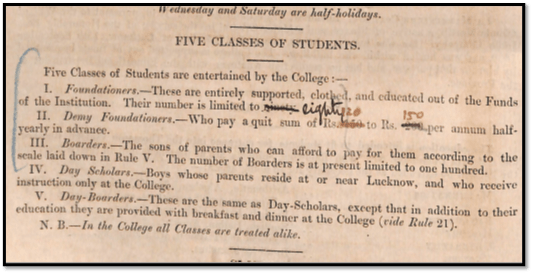

The first Prospectus of the College for the European Section was drafted, submitted and approved in October, 1869. An updated revised version, which included descriptive rolls of pupils was approved on 21 February, 1877. This contains the categories of pupils admitted to the College.

This four-page leaflet, printed at the American Methodist Printing Press, Lucknow included sections providing a brief overview of the history of the College, subjects taught in the College for preparation of pupils for the Thomason Engineering College, Roorkee and the Entrance Examination to Calcutta University. Other insertions included Distribution of Time, Holidays, Clothing, Rules and Regulations with a table of fees for Boarders and Day Scholars. This Fee Chart was a sliding scale based on the certified income of the parent. Other charges were included optional facilities like games, private tuition in French, German Greek and Music and Art.

By this time, the status of pupils had been established, with FIVE classes verified, with the special codicil that “In the College all Classes are treated alike”:

It was clarified that “The Institution has been authoritatively pronounced a Church of England School, but no undue influence with a boy’s creed will be attempted or allowed [Trustee’s Memo. of the 12th November 1862]”

DESCRIPTIVE ROLLS

In 1872, ‘Rules for the Internal Discipline of La Martiniere College’ were ‘Printed for Circulation among Officers in A.D. 1872”. This included Descriptive Rolls for all pupils. While the Rolls for Boarders and later, for Day-Scholars, contained standard information regarding identity, the Rolls for Foundation applicants were invasive and embarrassing.

Besides the formal details of identity, parentage, residence, income, occupation of father (including whether he was dead or alive), the information required included the legitimacy of the boy. In the event of the father being deceased, a declaration was required whether the mother had remarried, whether the stepfather was ready to contribute to the boy’s education, the number of dependents on the mother and how they were to be taken care of and if the boy was a ‘full orphan’.

Questions included, ‘Is the boy English in his habits? Can he speak and write English’; ‘Is the boy Eurasian or pure European?’. The information recorded included enquires about pensions, compensation to the College on leaving and whether the child would be taken home for the ‘long holidays’ from 15th August to 6th October. Finally, guardians were reminded “It is deemed advisable that all boys should visit their friends at least once a year. (General Rules XL)”

SCRUTINY OF THE FOUNDATIONERS

It was the norm to avoid admitting boys to the Foundation if the father had been in the British army, as the boy eligible for admission to the Lawrence Asylum, Sanawar.

It was the norm to avoid admitting boys to the Foundation if the father had been in the British army, as the boy eligible for admission to the Lawrence Asylum, Sanawar.

The Lawrence Asylum had been established by Sir Henry Lawrence in 1847, whose intention was to provide for the education of orphans, both boys and girls, of British soldiers and other poor white children. In the early days some Anglo-Indian children were admitted. Lawrence insisted that preference should be given to those of “pure European” parentage, as he considered they were more likely to suffer from the heat of the plains.

Therefore in 1873, it was found necessary to put additional questions to those whose fathers had served and died or were pensioners of the army.

Some of the questions included:

Has application been made for this boy to the Lawrence Asylum?

Has he been admitted to the benefits of “the Lower Orphan School”?

Was the mother within the authorized number of soldiers’ wives, and in receipt of subsistence allowance?

Is the boy’s mother still a widow?

It was not enough to seek written information, the material provided had to be certified by persons of authority, sometimes, twice a year.

To avoid or to minimize the use of forged documents and untrue responses, in order that those truly eligible for the benefits of the Foundation be elected, a precautionary procedure was implemented by guarantors or referees being required to recommend a candidate. In April, 1873, the following Order was implemented “That in future, no boy be elected to the Foundation of the College until answers to the printed questions are certified to be correct by the Chaplain of the station where the boy resides or by some other public functionary”.

Two years later, it was found necessary to increase vigilance by a demand for half-yearly reports on the condition of the Foundationer’s family. In July, 1875 it was resolved “That a Form be prepared and circulated half-yearly, to be signed by the Parents or guardians of Foundationers and counter-signed by a Minister of Religion or Magistrate of a District, shewing if any changes have taken place in the positions or circumstances of the parents or guardians of Foundationers or in those of the Foundationers themselves”.

DEMI- FOUNDATIONERS

The College had been promised an increase in grant by the Trustees of Rs 1000/- per month in 1861. The Trustee described this as “the largest amount that can with prudence be added to the present monthly allowance for the support of the College”. This was immediately allocated by the Governors for an increase of an additional five boys to the Foundation, along with subsidized expenses covering forty other boys in the boarding house. This subsidized support was gradually becoming a ‘demi’-foundationership. The ethos of the College was to pass on needy pupils whatever financial advantage could be gained. This was formalized on 21 March, 1861:

“That five more foundation scholars be added to the European foundation and forty boys be added as boarders on a payment of Rs 6/- per mensem to cover all expenses as soon as the extra monthly allowance for the support of the College is obtained.”

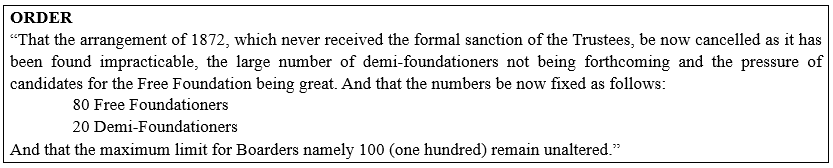

The term ‘demi-Foundationer’ was a later addition. While the number (100) had been fixed for Full Foundation pupils, there was generally an excess in numbers of applications, Such boys were admitted as ‘Supernumerary Foundationers’, so described on 9 March, 1876. They paid a subsidized monthly fee (in 1876) of Rs 10/-/- per month. Change to the Full Foundation was possible upon the recommendation of the Principal and the concurrence of the Board, though such change of status was rare. As a result, those who had the ability to pay limited fees continued to avail of the discount, leaving more deserving cases for the Full Freeships.

The term Demi-Foundationer (later reduced to ‘Demis’) became current from 21 June, 1878, when a review of the number of boys supported by the Foundation was carried out. The Governors resolved and reiterated:

INCREASE IN THE NUMBER OF DAY-SCHOLARS

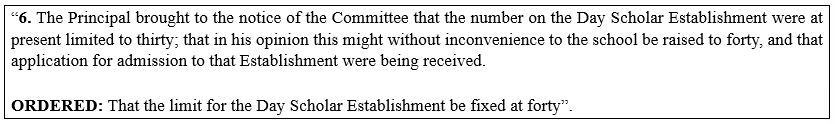

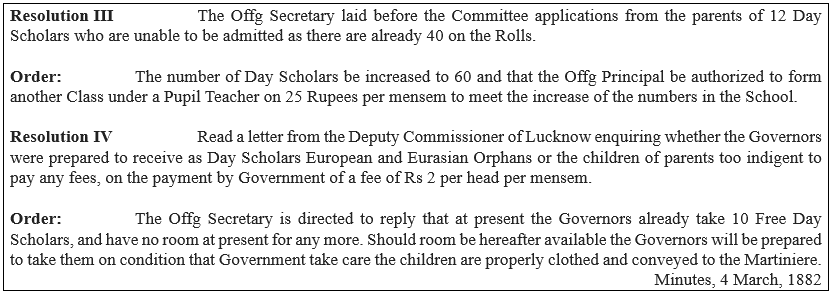

With La Martiniere College becoming more popular, it was found viable, 24 February, 1881, to increase the number of day-scholars to forty.

The demand for education began to increase towards the end of the century. Nevertheless, there was still ambivalence regarding the status that new admissions to the College would enjoy or the communities that could be admitted.

THE BRITISH EMPIRE

Queen Victoria was formally proclaimed Empress of India in 1 January, 1877. There was a certain arrogance, swagger and discrimination in all written communication from the College. La Martiniere College encouraged its pupils to be proud of Queen and country. The East India Company no longer had control over the funds of the Foundation and Martin’s bequests had to be re-examined and reapportioned. For example, money set aside for the release of debtors and prisoners of the East India Company, which had now ceased to exist, was alternatively to be utilized for the education of girls, using the precedent of the Girls’ school in Calcutta to justify this expenditure.

THE PRINCIPLE OF MERITORIOUS POVERTY

From time to time in the life of an institution, it is found necessary to recalibrate the raison d’etre for the establishment. Towards the end of the first half-century of La Martiniere College, this was summed up by Principal Stobart in his annual address in 1879:

Speaking of the guiding principle of admission to the Foundation, Principal Stobart coined the phrase ‘meritorious poverty’ and further presented an explanation:

Leave a comment