This is Part I of a FOUR-part series on the eponymous topic.

It is divided into sections for convenience in uploading and reading.

Part 1 deals with the first fifty years of the life of the College (1845-1895) and roughly corresponds to the time scale covering the establishment of the College to the turn of the century (1900)

INTRODUCTION

Claude Martin by Johann Zoffany

La Martiniere College, Lucknow, established by Maj. Gen. Claude Martin, H.E.I.C.S., has emerged as a behemoth on the educational scene in North India, largely due to the accretion of a series of factors that have helped to create its unique image. As a ward of the Court, it has neither been established by a Trust nor is it supervised by a Society. The estate extends to being one of the largest land banks for a single school in India. Its history includes the French, the East India Company, the Kingdom of Oudh, the British Empire and the Republic of India. It is the rare school to be permitted to carry a flag of honour presented in acknowledgement for contribution of its Masters and pupils during the Defence of the Residency in Lucknow. It is an institution that has adapted to change without ignoring tradition. It is a much-loved home for all who have studied or worked there.

Yet, despite these unique realities, the institution has been steadily reinventing itself. Once a purely European school, it is now made up of boys who are completely Indian. This transition and the change in demography are an interesting study that includes discrimination, charity, racial compulsions, law, ethics and above all the indomitable spirt of the adolescent boy.

The institution today is a legal entity, protected as an institution of the Anglo-Indian linguistic minority, seeking protection under Articles 30 and 31 of the Indian Constitution. It has nevertheless aligned itself by choice to praise-worthy practices and commitments encouraged by government for equity without losing sight of the core principles by which the institution was founded.

Throughout its existence in the controversial circumstances of history, there have been varied charges related to discrimination of different types. These include ‘negative discrimination’, i.e. unfair treatment to individuals, groups or communities, causing harm and inequality. ‘Positive discrimination’ is a term that can be misleading. It is a contested concept where certain groups are treated more favourably. This is often unlawful and can undermine the purpose of equity by causing ‘Reverse discrimination’ and resentment.

Yet, discrimination, positive or negative, is to be considered in the context of the times under consideration. On a national scale, there is evidence that there has been negative discrimination against certain communities; therefore, reservations for such groups, which have been brought into place after the adoption of the Constitution of India, may be seen as a means of converting such, negative discrimination, to positive protection through political representation and social repatriation. Positive discrimination through the system of providing privileges in opportunities for education at La Martiniere College, Lucknow to certain groups or communities, especially Europeans and Anglo-Indians, known loosely as ‘foundationers’ may be seen in this context.

THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE INSTITUTION

Claude Martin signed his Will on 1 January, 1800. Relevant to the establishment of La Martiniere, Lucknow are Articles 27 and 32 of the document:

ARTICLE 27

My house at Luckperra or Constantia house is never to be sold as it is to serve as a monument or a tomb for to deposit my body in and the house is to serve as a college or for educating children and men for to learn them the English language and religion those that should wishes to be made Christian.

ARTICLE 32

For to keep Luckperra house or Constantia house as a college for instructing young men in the English language and taking care of my tomb which house was properly my reason for having built it wanting at first to make it for my tomb or monument & a house for school or college for learning young men the English language & Christian religion if they find themselves inclined.

The enormous wealth of Claude Martin warranted fierce legal battles for about 40 years after his death, which occurred on 13 September, 1800. Eventually, on the orders of the Privy Council, a scheme of administration was drawn up and the College was established by a Decree the Supreme Court in Fort William, Calcutta on 22 December, 1841. This was based on the broad principles set down in the Will of Claude Martin:

The Court at Fort St William, Calcutta

“ … a College sufficient for not less than 200 scholars with a combination of boarding and lodging within the institution for at least one fourth of that number … this Court doth further order, decree and declare that admission to an equal participation in the benefits of the College be given without preference in respect of religion or sect and that according to the condition expressed by the King of Oudh in giving his permission to the Establishment of the College, those students only who voluntarily desire to be instructed in the Christian Religion shall be taught it and in conformity to that condition, no works on Christianity shall be admitted as Class books in the College.”

Constantia: Claude Martin’s country residence

La Martiniere College was founded in 1840, with classes commencing in 1845, when the buildings were suitably prepared to receive pupils. The institution was in an ambivalent administrative condition, located in prime property down the river Gomti, close to the palace of the Muslim Nawab of Oudh. The Christian British Resident was ensconced in the palatial Residency, a short distance from the Nawab’s Palace. The contest between the native Nawab and the Colonial powers also delayed the establishment of the College. The Nawab objected to a teaching of the Christian faith within his territory, acquiescing when convinced that the Will of Claude Martin clearly stipulated that the teaching of the Christian faith would only be offered “to those who desired”.

The Constitution of India (1950)

La Martiniere College, Lucknow continues to enjoy the privilege of this protection following the establishment of the Republic of India. The Constitution of India (1950) in Article 366 (2) defines an Anglo-Indian and provides certain safeguards for the protection of the said English-speaking linguistic minority community. This is especially relevant for the educational institutions established by Europeans, such as Claude Martin, the Frenchman who bore the rank of Major General in the Honourable East India Company Service.

Seal of the Supreme Court, Calcutta

The relevant Articles in the Will, the detailed Scheme of Administration and the commitment to refrain from proselytising, establish the protection of the boys supported completely by the foundation. This, in fact, forms the underlying ethos of the institution.

Ethos is the underlying character, the core beliefs, the guiding principles that form the foundation of a community or institution. This, in the case of La Martiniere College, Lucknow is ‘Charity’ immortalised in a significant line of the School Song – “All his Martial deeds may die: lasting still his charity”. This ethos, while abstract, is assisted by traditions that protect it. Traditions are the specific practices passed down through generations. If tradition is seen as the “what” that is done; ethos is the “why” or the fundamental spirit that drives it.

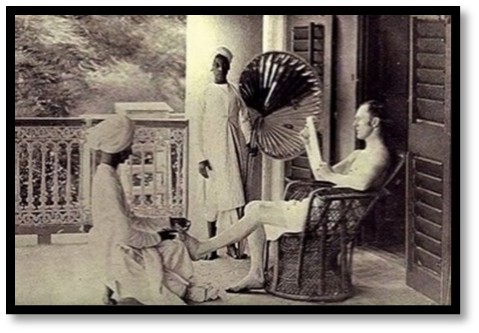

Again, the experiences of the Founder that influenced his decisions need to be considered to establish context for the establishment of the Institution. Education for Claude Martin was the paramount way to lift out a person from penury and disadvantage. Claude Martin himself received a rudimentary education, referred to in his Will. His advantage in progressing through life was the result of staying abreast with academic and practical pursuits. Consider his work as a cartographer with James Rennel, the father of cartography in India. Measurements, topography, operating apparatus, drawing etc were skills that were learned and imbibed. This placed him much ahead of his peers. He did have a deep respect for officers of the East India Company, men who had received well rounded educations for that time, which they used for the subjugation and colonisation of an empire controlled by an island mass that was trifling in comparison. As he grew older, not having children of his own, there was a silent respect for the ingenuity of children, which was often hampered by a lack of opportunity for education and of physical care.

Racial Discrimination

It is significant that even in an age where racial discrimination was prevalent and accepted, he provided equal opportunity for all races and communities, no doubt circumscribed by contemporary realities, like gender. The Lucknow bequest only envisaged a school for boys and men, with the studious omission of girls and women, perhaps due to the mores of a traditional, orthodox and conservative local society.

Later interpretations and machinations of the Will of Claude Martin made the institution he envisaged and the charity by which he was driven, moulded into convenient interpretations based on political requirement, racial discrimination, security and clashes in culture.

Constantia: 1814

The Will of the testator must be respected. It was after all his vision, munificence and wisdom to set down in writing and appeal to governments and courts in generations ahead to protect his interests. “I am in hope government or the supreme court will devise the best institution for the public good … as that it be made permanent and perpetual”.

It is part of the civilized world to adhere and respect this as enshrined in law, practice, convention and precedent. Claude Martin requested that a copy of his Will was “to be deposited in the Supreme Court, to which I recommend my executors, administrators, assigns, or trustees, to put this Will and Testament under theirs protection, or tender the protection of government if necessary;”

THE PLIGHT OF VULNERABLE CHILDREN

(James Martin ‘Zulpheekar’)

In the mid-19th century, there would have been absolutely no opportunity, for European and Anglo-Indian children to receive an education if the family lost the breadwinner or had domestic difficulties through separation, desertion, or other challenges. For such children not to descend to becoming ‘bazaar trash’ was only possible if special opportunities or a ‘quota’ was provided for them. This is what Claude Martin envisaged, especially by observing the white trash in the bazaars that had gone ‘junglee’ due to the lack of parental influence in their lives. One such boy was James, a Georgian lad in difficult circumstances. James had been born of a drunken father who came to Martin with a plea to return to Georgia, indicating the inability to do so due to a lack of money. He was willing to give up his son James into the permanent care of Martin, if he could be provided with financial assistance, to return to Georgia.

The story spun by the father turned out to be incorrect. He squandered on drink the money given to him by Martin. Whether he thereafter returned to Georgia or not is unknown What is recorded is that James was taken in to Martin’s household and even given his surname as a patronym. The child was adopted and cared for by Boulone-Lize, Martin’s young companion. Sometime later, James’ mother appeared on the scene with an infant son called Amodbeg. The boy James continued to be cared for by Boulone, while his birth-mother became a retainer in Martin’s household. The child James was given the alternative Islamic name, Zulpheekar. James was sent to Calcutta to be educated and as an adult conducted the affairs of the zenana in which he had grown up.

Perhaps due to his traumatic experiences as a child, his love for his adoptive mother who followed the Islamic faith, or his interaction with the wider society of Muslims, the boy vacillated between Christianity and Islam. He eventually died a Muslim in 1835, predeceasing his adoptive mother and before the institution that came to be known as La Martiniere was established. He was buried near the mosque that he had built, known as Gori Bibi ka Masjid in Peer Jalil Ward in Kaiserbagh.

Boulone-Lize and James Zulpheekar Martin

When we consider, the condition of James and the rag-tag of mixed ancestry that filled the bazaars of Colonial towns, we cannot but be moved by the strange fate and condition of such children. It might seem a romantic notion, but the story of James Zulpheekar Martin and the manner in which he was provided for by his benefactor, may be seen as a part of the motivation to establish these schools. To sustain this claim, consider that Article 9 of Martin’s Will tells of Zulpheekar being sent to Calcutta to be educated. Almost the same words are used in delineating the foundation of the school in Lucknow. They include: the study of the English language; the study of the Christian faith; the choice to be exercised by the beneficiary.

Article 9: “… and when he (James) became a tall boy, I had him put at school at Calcutta, for to learn to read and write English, as also to learn the Christian religion, that he might choose whether the one or the Mussulman, or any he may choose; he preferred the Christian, he and he was Christened in Calcutta church by the name of James.”

Article 27 echoes similar language “a college, or for educating children and men for to learn them the English language and religion; those that should wishes to be made Christian at or by that house.”

(Boulone-Lize & Sally Harper)

Boulone (Boula Begum)

Even more arduous would have been the survival of the vulnerable girls. Even during his lifetime, Martin had donated to charities for orphan girls in Calcutta and Madras. More specifically, the condition of two of his female companions indicate him being moved by the condition of abandoned children. The antecedents of Boulone-Lize (Boula Begum), declared by him as his favourite companion, indicate a case of child abandonment. Boulone was of noble birth; her family being connected to the Mughal court in Delhi. At about the age of nine, under disturbing circumstances, she ran away when it is reported her father murdered her elder sister in an honour killing.

The other girl, among the seven women he had as part of his establishment was Sally, an illegitimate child, said to be fathered by the one-time Resident of Lucknow Colonel Gabriel Harper. Sally would never be acknowledged by her father and under other circumstances, she would have been ostracised. There are several examples of exploitation or neglect of children. Claude Martin himself made commitments to take care of native families of European men who were his friends, who decided to return to Europe, leaving such women and children to largely fend for themselves. Providing opportunity for abandoned children, could be seen as positive discrimination and an opportunity for a better life for such children.

Martin’s biographer, Dr Rosie Llewellyn-Jones comments: “Life for abandoned or abducted girls, especially those of mixed blood was precarious enough, even if they did not starve to death during famines or end up in brothels”. The same was probably true of boys.

The boys, European, Anglo-Indian or native, were more advantaged. By means of an education, they could advance in life in a manner similar to Claude Martin himself. But such boys were also constrained by circumstances, the alleviation of which could be encouraged by education. European and Anglo-Indian boys were not only sons of officers. They were, in the case of Europeans, sons of low-ranking soldiers, men in the subordinate services of the East India Company or half orphans, without the financial means to return to Britain. In short, boys who bore all the physical characteristics of their race but who had descended to the flotsam and jetsam of the bazaar. Most strikingly, they even lacked a knowledge of the English language, one of the passports to success. The loss of their native language was the result of having to struggle to survive in communities that were different to their racial, cultural and linguistic stock.

(Native Children)

Conscious of the condition of all children in such circumstances, Martin did not restrict the privileges extended by him to people closely associated to his race. These benefits were to be applied in the case of native children; to give them a leg up through the transforming influence of education. La Martiniere was envisioned to be accessible to young men and boys, irrespective of their faith.

Seeing native children in difficult conditions, brought on by no fault of their own, Martin was perhaps moved to bequeath his vast wealth primarily for the education of such children, both boys and girls. This education would materialise by means of his Foundation. It would be financially possible to provide such children with a haven along with a chance for a better life in the world into which they had been unwittingly born.

Martin’s charity towards children and education was not restricted to Lucknow. Lucknow was a traditional and orthodox city. It was only practical to establish a school for men and boys. In the cosmopolitan Calcutta, equal bequests were made for the establishment of two institutions, each for boys and for girls. In Calcutta, there would have been a much larger number of illegitimate or abandoned children and orphans, both boys and girls who would benefit from such a bequest.

It is the practical establishment of a Foundation that made this charity a reality. Martin, vide his Will appealed to governments of the future to regulate the application of his wishes. Every residual benefit from the property and investments as declared in his Will were to be used for this prime objective:

“After every article of this Will and Testament is or are fully settled, and every articles provided and paid for the several pension, or the gift, donation, institution, and other, any sum remaining may be made to serve – first, buy or built a house for the institution, as that it may be made permanent and perpetual, by securing the interest by government paper either in India or Europe, that the interest annually may support the institution; for this reasons I give and bequeath one hundred and fifty thousand sicca rupees more, according to the proportion that may remain after every articles of this Testament is fulfilled, then this sum to be added for the permanency of that institution …”

Leave a reply to SSoi Cancel reply