THE RUN UP TO INDEPENDENCE

Months before Independence, on 16 October, 1946, the final bastion was breached when the Governors made an exception for the first Indian boarder to be in residence in the College, although as an unprecedented exception:

Resolution 91/46

As an exception the Governors’ Resolution 32/40 dated April 20th, 1940, it was agreed that V. Bharucha, a scholar of Class IX and for seven years’ a day-scholar, might, as a special case not to be regarded as a precedent, be admitted as a boarder on the transfer of his father from Lucknow.

Minutes, 19 October, 1946

Indian students had been unwilling admitted and then condescendingly acknowledged in the run up to Independence. These admissions were exclusively for day-scholars. Despite the Government requiring the College by repeated letters, to “alter the rules so as to allow of the admission of Indian Boys as boarders,” the Committee steadfastly refused, citing “extremely limited accommodation and the over-riding needs of the European and Anglo-Indian Boys.” The Minutes of the Governors of 11 January, 1947 record the argument: “to keep the percentage allowed, they could not be so admitted except by reducing the number of Indian day-scholars which would be hard on residents of Lucknow.”

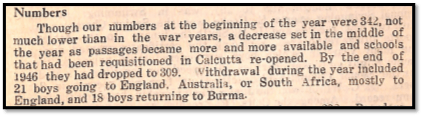

Contemporary history, including the diaspora surrounding Independence further changed the composition of the student body. Looking back on the previous year, Principal W. E. Andrews reported on the developments in his Annual Report presented in March, 1947:

Independence was marked by silence. The last meeting of the Committee in British India was held on 9 August, 1947, within the week that Independence was declared. The first meeting of the Committee in Independent India was held on 20 September, 1947. Significantly, the first changes noticed was in the profile of the student body. The change was slow and propelled by the reality of the Indian state as well as by economic reasons. Changes in language, demography and religious observances were introduced by law.

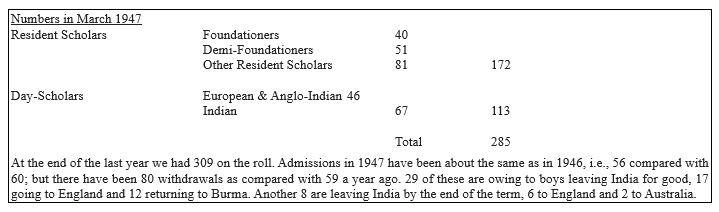

The last headcount before Independence was recorded on 31 March, 1947 as reported in the Principal’s annual Report:

The immediate upshot of these reduced figures was the immediate provision for the admission of Indian boys to make up 15% of the Boarding House strength.

Resolution 60/47 Resolved that in view of the boarding house now having vacancies for their admission the Principal might admit Indian scholars as boarders up to 15% of the total number of boarders.

Minutes, 9 August, 1947

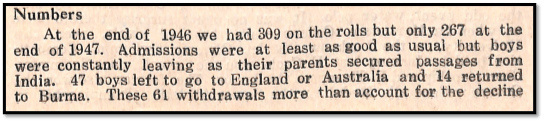

The trend of withdrawals due to migration continued in 1947, and by December of that year, the Principal once again reported:

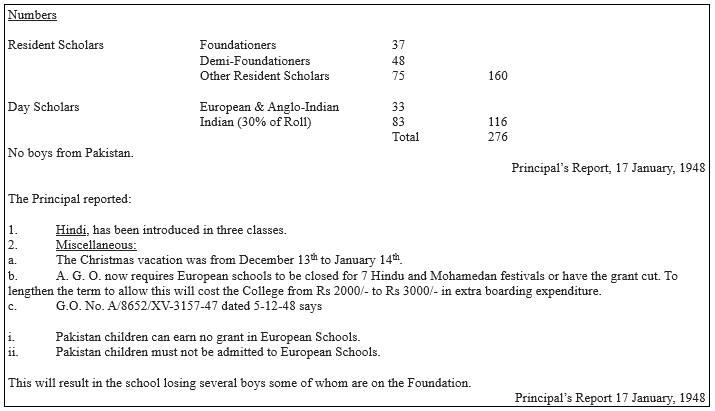

By the end of 1947, the demographics had changed. Resident Scholars now included Indian boys, and the number of Indian day-scholars was now at 30% of the total strength:

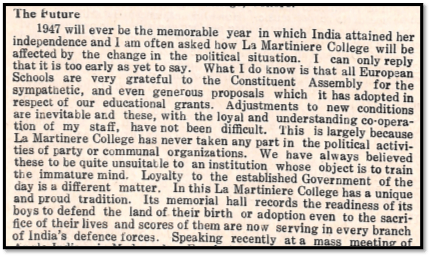

It is significant to ponder on the words of Principal W. E. Andrews, whose message is a contempory record of the changes taking place in La Martiniere College, Lucknow; the most momentous for the Institution after the events of 1857, some 90 years previous. His remarks summarise the attitude towards the new dispensation with which this once very European school now had to contend:

IN RETROSPECT

Between 1900 and 1947, the character and student body of the College was shaped by wider social and political change. As education became more formalised the College adapted to new accreditation and credential expectations; racial segregation policies and social hierarchies continued to limit access and preserve privileges for Europeans and Anglo-Indians; rising nationalist movements and the struggle for Indian independence created political and cultural pressure on institutions; and increasing competition on merit highlighted tensions over the special privileges long enjoyed by Europeans and Anglo-Indians. The period was one of institutional adjustment where educational standardisation, entrenched social hierarchies, nationalist change, and rising meritocratic pressures combined to redefine the College’s demographics and role in a transforming India. Principal Sykes outlined realistic post-school pathways: subordinate administrative, postal, telegraph, forest, railway, medical and public works posts for most pupils; more gifted boys could aim for finance, surveying, engineering, or commissions via military/medical examinations in England. He warned Europeans in India that failing to qualify would let native candidates take those opportunities.

- Expansion of other colleges and schools reduced La Martiniere’s monopoly. The rising demand for general intermediate education increased admission pressure while existing racial quotas and fixed percentages constrained intake. Administrative reviews and external reports forced reforms in status, finances and educational aims, aligning La Martiniere with wider British-school educational trends in India, culminating in adjustments influenced by educational reforms such as the Barne’s Report and the Sargent Scheme.

- Racial segregation was influenced by maintaining a strong Volunteer Corps and cadet tradition intended to preserve its European identity by training British and Anglo-Indian boys as a reserve force. Military training reinforced the College’s European character and social separation from native communities. The College’s long-standing cadet and military programme shaped alumni career paths into the armed forces, created a durable culture of discipline and drill, and left a direct institutional lineage from 19th-century Volunteer units to the post-independence NCC.

- La Martiniere College, Lucknow followed a policy of racial exclusion that gradually softened, moving from explicit refusals of Indian pupils to conditional admissions under pressure from social and political change. In 1920 the Committee allowed boys “of good family” to be admitted but only as day‑scholars. Admissions remained weighted toward professional and land‑owning Indian families. The record shows a trajectory from explicit racial exclusion to reluctant, conditional inclusion shaped by broader political change in India; concessions were often qualified by religion, social standing, fees, and whether candidates served the School’s image. Progress toward inclusion was incremental and conditional: legal quotas, religious segregation in boarding, social status, language expectations, and external events such as politics and war, all shaped who could join and under what terms.

- Large post‑war and pre‑Independence withdrawals with boys emigrating to England, Burma, Australia, thereby creating vacancies that forced a policy shift: in August 1947 the Principal was authorised to admit Indian boarders up to 15% of total boarders. Radical change came through demographic and political upheaval rather than voluntary liberalisation. Policy changes from late 1946 through 1947 converted reluctant, conditional admission into formal inclusion within set quotas, while state directives and migration continued to reshape the College’s communal and linguistic profile.

- Regrettably, the College failed to reinterpret Claude Martin’s Will to match changing social and economic realities, harming the intended beneficiaries — the Foundation pupils.

- Trustees and Governors adhered to the letter of the Will and original Scheme of Administration, while abandoning its spirit: funding, strategic investment, and transparent stewardship for Foundationers were neglected. Foundation pupils came to be viewed as a financial burden rather than the core beneficiaries of the founder’s “lasting charity.” The symbolic quota of 100 Foundation pupils (fixed in 1859) became a rigid lodestone rather than a proportionate share of an expanding student body. The College grew from 200 pupils in the 19th century to several thousands; yet the Foundation’s numbers remained essentially static, creating ambiguity about how many boys should meaningfully benefit. The piecemeal tinkering preserved formal compliance while undermining charitable intent: real financial support, capitation, and domestic measures for Foundation pupils were insufficient. Foundation benefits became tokenistic, obscured by administrative manoeuvres that prioritized institutional form over substantive welfare of deprived pupils. La Martiniere’s governance consistently prioritized legalistic conformity and colonial social norms over adaptive fiduciary stewardship; as a result, Claude Martin’s charitable purpose was diluted, leaving Foundation pupils ill-served through the twentieth century.

In the decades before Independence the Anglo‑Indian community at La Martiniere was foregrounded as a distinct beneficiary of the College, yet also repeatedly counselled by authorities to adapt and integrate into a changing political and economic order. A string of high‑profile Chief Guests and governors used Prize Day addresses to reassure and advise the Anglo‑Indian community—urging education, vocational preparedness, and integration into public and industrial life rather than retreating into privilege. Speakers, including Trustees, Governors, and Principals, combined encouragement with realism: they praised the community’s place in the school, warned of looming social change, and recommended competitive adaptation through training, skill development, and public service. The repeated public reassurances aimed to steady a community facing uncertain prospects, but they also reflected an implicit message that Anglo‑Indian advantage could not be assumed — survival would depend on adaptation, education, and vocational readiness as Independence reshaped opportunities.

Leave a comment