RACIAL DISCRIMINATION

A studious rejection of all applications for admissions of ‘Indian’ pupils was made till the beginning of the 20th century. With greater incomes, accesses to international trends, global travel and awareness of the advantages of formal education, more Indians kept clamouring for admission to this very European school.

As early as 1904, not very subtle refusals were made unapologetically. It was clear by the superscription: “Natives not admitted.”

The great divide in demographics was supported by Government policy. At the Domiciled Education Conference of 1912, the Definition of the Community and the privileges sought by them was spelled out.

“The definition of the members of the domiciled community had been raised in the opinions submitted. The definition as given in paragraph 2 of the Codes was reasonable and should be allowed to stand. The Code made provision for the admission of a certain percentage of Indians. There was no intention to alter such provision. It was necessary, however, to see that this percentage is not exceeded and that such schools are not invaded by children of purely Indian descent, who pass themselves as Anglo-Indians.”

The term of the day to define a non-European was ‘native’, a label that post-Independence has pejorative connotations. With greater demands for independence, the mindset of the European was compelled to change. On 10 May, 1917, the appointment of a non-European Science demonstrator reflected this change. Referring to his appointment he was described in the Minutes of the meeting that day as ‘a native’, a phrase that was struck out and replaced by the term ‘an Indian’. This correction was also initialled by the Chairman of the day, B. Lindsay:

The early 1920’s was a confusing time for the Governors of the College. Applications for admission of Indian children were first summarily dismissed by the Governors. The Chairman of the Committee was Mr B. Lindsay, ICS, appointed in January, 1920. Lindsay had advised the Government regarding the major anti-British campaign in India called the Khilafat Movement led by the brothers Muhammad Ali and Shaukat Ali. Applications for admission for boys of Indian parents or of mixed parentage were unlikely to be considered.

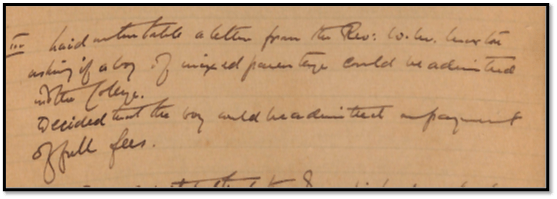

Surprisingly, on 14 February 1918, a concession was made for the admission of an unnamed boy who was of ‘mixed parentage’. In his favour, the boy had been recommended by a Rev. W.W. Merton, and it is presumed that the boy was a Christian. The boy was permitted admission on the payment of full fees.

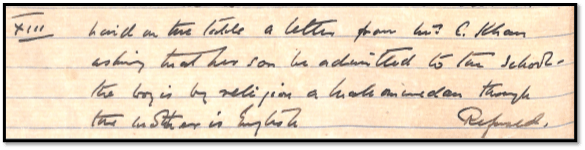

In March, 1920, Mrs E. Khan, an Englishwoman applied for admission for her son who followed his father’s Islamic faith. Such a union, seen as miscegenation, was frowned upon. The application was outright refused.

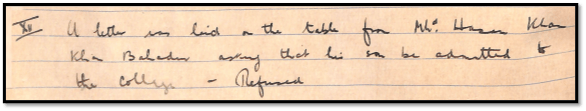

A month later, Khan Bahadur Mohammad Hasan Khan applied for admission for his son. The father of the boy had been awarded the honorific title of ‘Khan Bahadur’, a title granted to individuals for distinguished service to the British Empire or for public welfare. This sign of high honour, albeit below a knighthood, was accompanied by a Title Badge. Nonetheless, on 8 April, 1920, the application was refused. It was the last time that an outright refusal was made on grounds of race.

Significantly, four months later, the same Committee was obliged to acknowledge the changes in the times when on 12 August, 1920, the same Committee that had rejected applications of Indians, now resolved differently, with a face-saving condition that Indian boys must come from ‘good families’ and that they would only be admitted as day-scholars:

Resolution XIV The Secretary reported that he had some applications from Indians for admission. These were boys likely to go to England and wishing to study for their Senior Cambridge Certificate. It was resolved that boys of good family might be admitted subject to approval of the Committee and only as day scholars. The fees to be Rs 20/- per month.

Considering the changes that were sweeping over India, the Committee on 4 November, 1920 agreed to admit Samuel Pant, the grandson of an Englishwoman, though his father was an Indian. He was admitted as a Boarder on full fees. A saving grace was that the boy was a Christian, a fact recorded in the Minutes.

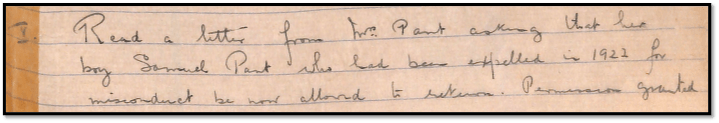

The change in overall attitude in the College was reflected in the decision to readmit Mrs Pant’s son, who had been expelled for some misdemeanour in 1922. The circumstances must have been exceptional as on 24 February, 1926, four years after the incident, the Committee was approached for readmission of Samuel Pant. This was liberally granted.

Leave a comment