THE GIRLS’ ESTABLISHMENT

Even as the College was grappling with the decline and closure of the Native School, the demographics of the institution underwent change with the setting up of the Girls’ Establishment. A ‘Dame’ school, run by Mr & Mrs Abbot in Lucknow, went bankrupt. An appeal was made to the Local Committee of Governors to take over the teetering establishment, which would otherwise result in European and Anglo-Indian girls being abandoned.

In an unprecedented move, on 10 July 1867, the Visitor of La Martiniere College, along with every Member of the Local Committee of Governors sent a suo moto petition to the Trustees for the establishment of Girls’ School for European and Eurasian girls, rather than for the ‘native’ female population as was proposed by the High Court from the funds that were available from General Martin’s Will following the East India Company ceding to the British Government. In a strongly worded recommendation, they took upon themselves the onus of pioneering a school for girls in Oudh:

“We find though that this is not want of funds or of energy, on the part of the promoters that has rendered. the results of the efforts already made so little satisfactory; but it is the apathy of the native community whose benefit it is sought to secure. It is the bigotry of parents, their fear of this new matter and the dead weight of the prejudices of the past ages against which the promoters of female education in this part of India have to contend.

We fear that the establishment of a School under the immediate management of the highest officials of this Province would, increase these prejudices and add to the difficulties of those at our quickly, but as we hope surely, making progress towards the general diffusion of this inestimable advantage. We fear that for some years such a School would prove, a dead letter or would practically defeat its own object. We, with regret, have arrived at the conclusion that the time has not yet arrived when the Scheme for the promotion of Native female education, such as is contemplated in the Order of the High Court of Judicature, above referred to, can advantageously be introduced into Oudh.

But they are other classes of girls to whose education and benefit was equally dear to the magnanimous heart of the founder of these noble charities, and for their benefit, the additional funds at the disposal of the High Court, might most advantageously be applied; not only generally in India but here at Lucknow and in every station of the Province of Oudh in which General Martin served and died.

We have very large and growing number of English and Eurasian girls, whose parents have little or no means of obtaining for their children a sound practical and Christian education. More than that, there are now in this station within our knowledge, three English girls for whose education and maintenance no one is responsible.

As Railway employees and European soldiers are discharged in this country, the number of such cases must increase and it is terrible to think of the future fate of such, should the parents be removed by death and the children left to the mercy of the native servant or the stranger.

An establishment similar to the existing College of boys might receive as free boarders often such as those described above and would secure to the daughters of Clerks, old soldiers and other Christian members of the Community that education which is now afford to their sons.

We have every reason to hope that should the High Court of Judicature sanction this modification of their order by the erasure of the word ‘Native’ before ‘female education’ and by sanctioning the outlay of a portion of the capital for building purposes, this noble contribution from the funds of the Martin Charities would be doubled by a donation from Government from the public funds. The late amiable and venerable Lord, Bishop of Calcutta has recorded in his Report of the funds for establishing Hills schools for 1865 that “the Government of India has wisely and generously encouraged the project by promising to double from the public revenues all money that is contributed towards it, a promise, which at the same time proved the value which Statesmen attach to it as was indeed more emphatically stated in the Minute by Lord Canning dated 29 October 1860.”

We would further note that a Girls’ School similar to that proposed for Lucknow exists under the Management of the same Board as the Boys School of the Martiniere at Calcutta and we would urge that here also that special weight will be given not to comparatively well to do classes, but to Orphans or the daughters of Europeans of an inferior class and Eurasians Clerks on small salaries. The members of this class are resident in the plains and have neither means nor inclination to send their daughters to the Girls’ Schools established in the hills.

Should the High Court of Judicature, on your recommendation, sanction this modification of its former orders, we are prepared to come up with a Scheme for the incorporation of the only existing School of this sort whose funds are utterly inadequate to supply the pressing education wants of these classes of the Community and which now under the management of a Ladies’ Committee, consisting of the wives of the highest Resident officials of the Province, vainly tries to supply this great want.

And we earnestly hope that this proposition will meet with your approbation and your support.”

In the interim, leading to a formal recognition of the Girls’ Establishment, the Girls’ School was supervised by a ‘Committee of Ladies’ “consisting of the wives of the highest Resident officials of the Province”. Once the legal formalities were in place, the ‘Ladies Committee’ was disbanded and the supervision of the Girls’ School was directly conducted by the Local Committee of Governors. The Principal of La Martiniere College served as Principal of the Girls’ School along with being the Secretary to the Local Committee of Governors. The day-to-day affairs of the new institution were conducted by a ‘Lady Superintendent’ who reported to the Principal.

The Secretary read a letter from the Hony. Secretary Girls’ School Lucknow urging on behalf of the Committee of the Girls’ School, the necessity of the Governors of La Martiniere College “at once taking over the management of the Girls’ School.”

In the same letter The Hony. Secretary lays before the Governors a statement of the present position of the Girls School and recommends that Miss Dixon the late Head Mistress should be asked to again accept the post of Head Mistress.

On these and other points, the Committee resolved:

1 That the Visitor and Governors of La Martiniere College Lucknow take over charge of the Lucknow Girls School (in anticipation of the sanction of the High Court of Calcutta and of the Trustee to the revised Scheme forwarded to the Trustee on 18th May 1869) from the 1st June 1869.

5 That communication be entered into with Miss Dixon the late Head Mistress with a view of again securing her services in that capacity and that, should that lady be willing to accept the appointment, it be offered to her on the increased salary of Rs 200 per mensem from 1st June 1869.

Colonel Barrow kindly undertook to see this resolution carried into effect.

6 That Resolution I be brought to the notice of the Ladies’ Committee and that they be informed that the Governors of La Martiniere having taken over the management of the Girls’ School under the revised Scheme, the responsibility of the Ladies’ Committee ceases from this date, and they are released from further care and anxiety in the matter. Also

That the thanks of this Committee be conveyed to the Ladies Committee for the past valuable exertions on behalf of the Girls’ School

Minutes, 3 June, 1869

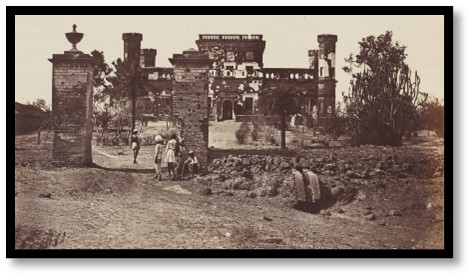

The Girls’ establishment was housed in the former 32nd Regiment Mess House that had suffered much damage during the Mutiny.

A year after the Establishment of La Martiniere Girls’ School, the first combined Prize Day and Founder’s feast was held on 15 December, 1870. It was a tradition that continued for over a century when the numbers in each school made it impractical to carry on.

Resolution VII Resolved that the Girls of the Martiniere Girls’ School have their annual Feast with the boys on the 15 December at the College and their prizes be given to them on the same day as the boys and the Report of the Girls’ School be read etc. That they all, Boarders and Foundationers, dress in a uniform manner. That the Ladies’ Committee be requested to design a suitable dress.

Minutes, 4 October, 1870

The antecedents of the Girls’ establishment were summed up by Principal Stobart in the Annual Report for the Girls Department in 1871:

The turn of the century was marked by the establishment of La Martiniere Girls’ School as an independent entity. The Ladies Committee, which reported to the Governors of La Martiniere College was replaced by the Girls’ School Committee, which consisted of the ex-officio Members of the College Committee with the addition of the Principal of La Martiniere College as a Member.

In 1908, the umbilical cord with La Martiniere College was severed when Mr Gaskell-Sykes tendered his resignation as the Honorary Secretary to the Girls’ School, a post he held for 23 years. The separate posts of Lady Superintendent and Honorary Secretary of the Board develved upon Miss J M. Bulkeley Willims who by 1909 was designated as rthe Lady Principal of La martiniere Girls; School. The demographics of the entire institution were once again altered.

THE WRITER’S COMMENTS ON PART 1

IN RETROSPECT

La Martiniere College, Lucknow, founded by Major General Claude Martin, has played a significant role in the educational landscape of India since its establishment in 1840. Its unique status as a ward of the Court, rather than a Trust or Society, and its large estate have contributed to its distinct identity. The institution’s founding principles, rooted in Martin’s Will, emphasized education in the English language and Christian religion for boys who so desired, while explicitly avoiding religious discrimination in admissions.

The College’s demographic composition and policies even in the first half century of its existence reflected the complexities of colonial society. Initially, both European/Anglo-Indian and native (Hindu and Muslim) boys were supported by the Foundation, with the latter group forming a separate Native Department. Facilities, curricula, and daily life were segregated by race and religion, mirroring the broader context of British India. Over time, however, the balance shifted, with increasing preference and numbers for European and Anglo-Indian students, particularly after the events of the 1857 uprising, which led to the disbandment and eventual closure of the Native School in 1876.

The College was committed to supporting boys from disadvantaged backgrounds, a principle evident in the admissions and ‘Foundationer’ system, as well as the introduction of ‘demi-Foundationers’. Despite stated ideals of non-discrimination, practical decisions often reflected prevailing biases regarding race, class, and language. Notably, knowledge of English and conformity to European habits became key admission criteria, further entrenching the institution’s European character.

Throughout its early decades, La Martiniere adapted to changing circumstances and needs. The upheaval of the 1857 Mutiny saw the College’s European and Anglo-Indian students take refuge in the Residency. With the School reestablished after the Uprising, financial adjustments, such as the introduction of sliding-scale fees, capitation payments, and exhibitions, helped to stabilise and expand the College.

Institutional developments which included the establishment of military training through the Volunteer Cadet Company was a response to contemporary needs. The eventual creation of a Girls’ School in the late 1860s, responded to the needs of European and Eurasian girls in the region. Administrative practices became more formalised, with descriptive rolls and rigorous verification of candidates for Foundation support, often probing into family backgrounds and eligibility.

By the end of its first 50 years, La Martiniere College had evolved from an inclusive, multi-community institution into one that more closely reflected the priorities and prejudices of colonial society, focusing predominantly on the education of European and Anglo-Indian boys and, later, girls. Its ethos of charity and support for ‘meritorious poverty’ endured, but was increasingly defined within the boundaries of race, language, and social standing. The closure of the Native School and the expansion of facilities for European students marked a significant demographic and cultural shift that would continue to shape the College’s legacy in the decades to follow.

No institution that must survive can remain static. La Martiniere willy-nilly responded to the needs of the times. From the turn of the century to the mid-20th century, the demographics of the College underwent unforeseen change.

Leave a comment