A single man’s bounty, well-invested funds, a consciousness of the spirit of charity that is the underlying ethos of the Founder’s bequest has made it possible for many to be educated. This, it was hoped, would be in perpetuity. The obligation lies in solemn trust of those who in an unchanging sequence are called upon to act as stewards of his Will. Indeed, this solemn stewardship has been largely honoured. The school in Lucknow was established 40 years after his death, precisely because the executors called upon to implement his Will, determined that despite all attempts by various forces to garner some part of his vast estate, Constantia House would, vide Article 27 never to be sold “and the house is to serve as college for educating children and men in the English language and religion. Those that wishes to be made Christian”. The same sentiment was recorded in Article 32: “for to keep the said Constantia House or College for learning young men to English language and Christian religion if they feel themselves so inclined”. Further, in Article 33 he determined that the school would continue in perpetuity – “the establishments of Calcutta, Lyon and at Lucknow, as that they may be permanent and exist forever”.

Martin’s Will, though exhaustive is also rambling. The details of individual bequests, gifts, investments, lists of properties, and so on is expansive. When it comes to fitting this into viable dimensions, it was left to the Court at Fort St William, Calcutta to be instructed by the Privy Council to lay down a Scheme of Administration. The broad outlines of the Will were codified in practicable terms. The Decree establishing La Martiniere College, Lucknow determined that to begin with, a school for 200 boys would be established, of which 50 would be in residence. It was clear that these fifty boys in residence would be taken care of by the Foundation and the term ‘Foundationer’ came to be used to define them. It might also be assumed that the 150 other boys, both European/Anglo-Indian and Native would be educated free of cost.

It is a matter of controversy as to how Martin intended his bequest to be utilized for the education of boys. The Will is silent on the race of the beneficiaries, leading to various interpretations of his intentions. Martin in his Will had stated that either Muslim clerics or Christian priests were to instruct the boys. The Scheme of Administration decreed: “That the Establishment shall at least consist of one Principal of the College, one head teacher in the English Department, one Arabic, one Persian Maulvi”. The nationality or race of the boys to be admitted was not specified. It was specified in the Scheme of Administration that “this Court doth further order, decree and declare that admission to an equal participation in the benefits of the College be given without preference in respect of religion or sect”.

“To learn the English Language” a key phrase in the Will, may be interpreted as teaching the English language and western education to those who presumably did not have these language skills or who were not exposed to western knowledge. This would clearly point to the ‘native’ population, though it could also include European and Anglo-Indian boys who by their circumstances had fallen away from the stream of western learning and ideas.

“To learn the Christian Religion to those who desire” a linked key phrase in the Will points very directly to boys who were not Christians by default, through baptism in infancy. Once again, this points to the ‘native’ population which was not widespread Christian by choice. Vide this interpretation, La Martiniere College, Lucknow was intended for the ‘native’ population, where specifically there were to be no restrictions in communities seeking admission; a fact also endorsed by the Scheme of Administration laid down by the Court, which deserves quick repetition: “this Court doth further order, decree and declare that admission to an equal participation in the benefits of the College be given without preference in respect of religion or sect”.

THE FLEDGLING YEARS (1845-1857)

The corpus of the school, made up of 112 pupils on the first day, included 95 pupils who were part of an informal school, described as a “Reading School”, conducted by a Mr Archer, who also joined the Staff at La Martiniere. It is presumed that the ‘native’ students were all day scholars, as no provision was made for their accommodation till later. The remainder of the pupils were European or Anglo-Indian. All pupils were completely supported by the Foundation known as the Martin Charities.

The native pupils decreased in number, we are told, having been under the misapprehension that their attendance at La Martiniere would be rewarded with a stipend. It must be recognized that not much importance was placed on education in general; attendance at La Martiniere was inconvenient, as the premises were much removed from the native city.

Once numbers began to stabilise, it was formally decided to allocate a specific number of boys who could be taken care of by the beneficence of the Foundation, based on the funds available. Demarcation for native pupils and European pupils was neither considered in the Will of the Founder or Scheme of Administration of the Court. Yet, as soon as the school began functioning, discrimination asserted itself. The foundation of the demography of the institution was established. This would have repercussions in the decades to follow.

The Trustees found it convenient and practical to stick to the letter of the law and provide education, with complete support from the Foundation, to underwrite expenses for native boys. Neither did the Will of Claude Martin mention, nor did the Scheme of Administration lay out that the separate racial communities should receive instruction, boarding and lodging together. Therefore, a completely acceptable compromise was worked out: this European controlled school would also consist of a separate ‘Native Department’. This Native department, though within the precincts of Constantia House was separate. In this manner, education was provided to all communities, the foundation took care of the expenses of all, Constantia House was fully occupied as a school, albeit with different sections.

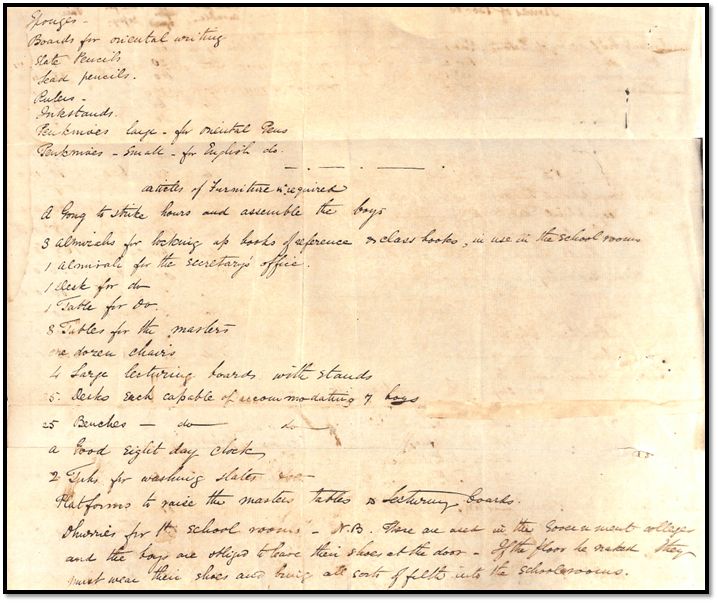

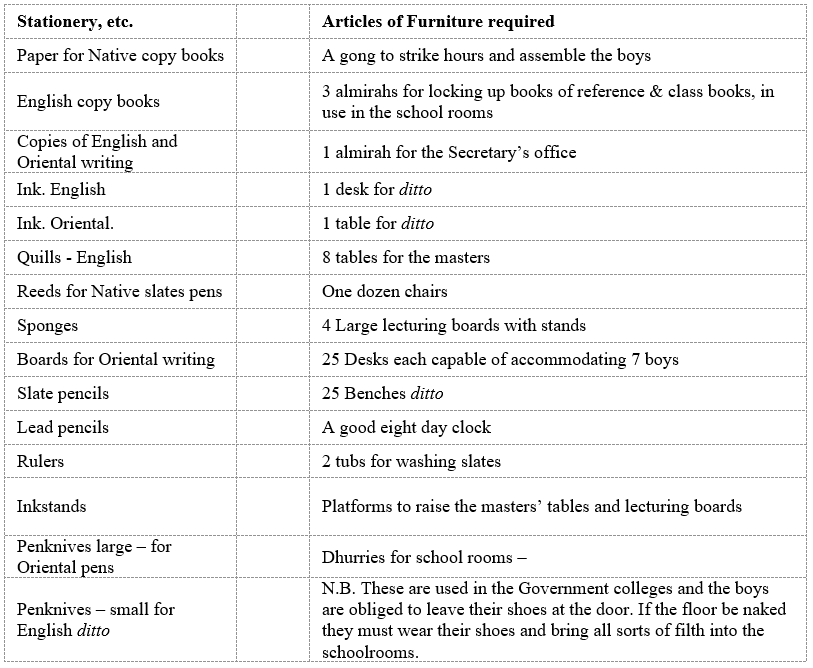

There is no record of there being any interaction between the communities of the two groups of boys. Boarding, lodging, diet, curriculum, instruction, furniture and apparatus were different. The list of items first required by the two ‘departments’ is on record. The items indicate the difference in the requirements for European scholars as contrasted with native scholars: Copy books vs slates; quills vs reeds; English ink vs oriental ink; desks and benches vs dhurries for seating.

It was presumed that the initial number of boys to be admitted would be between 120 and 150. This included both European and Eurasian boys and Hindus, Muslims and Christians, in what was referred to as the Native Section or Oriental Department.

The areas for the European and Native Schools were also demarcated. The Native Students were accommodated in the South Wing while the others were set up in the North Wing. Classrooms and teachers were different. The establishment was different. Books were different and even the requirements for the setting up of classes and what could be described as teaching aids were different.

Books were hard to come by. They had to be sourced from distant Calcutta and the red-tape involved in the setting up a new institution under the direct supervision of the Court in Calcutta made every member of the Committee wary. In a prognostication for the spirit of the College, Principal Newmarch in a Circular of 12 November, 1845, a little over a month of the foundation of the College recorded “I may state meanwhile for the satisfaction of some members of the Committee that among the books which I have selected there is no work of Religion or Politics”.

The Will of Claude Martin expressly states that there would be no discrimination based on faith professed. This ideal would have been impracticable in the social, cultural and political environs of the time. Using prevailing contemporary bigotry, it was conveniently interpreted that the Institution would display a preference for European and Anglo-Indian boys.

Such apartheid, it seems, was completely accepted. In addition, kitchens for the preparation of meals were different as were systems of medicine. A Native doctor occupied Mahal Serai and it was found suitable for the Trustees to establish an account for the upkeep and pension of the native doctor.

The character of the Institution is moulded by those in charge. In 1852, Lt Col Sleeman, Resident at Lucknow, wrote the Trustees of the Lucknow Martin Charities in Calcutta in this regard. Dr Mowat, a Medical Officer sent by the Trustees in Calcutta, was travelling to Lucknow to report on the status of the Lucknow Martiniere. It was his task to report on the kind of education most suited for the institution. Sleeman’s opinion in this regard is recorded:

Gentleman,

… Globes, Atlases, instruments for observation and survey, model machines, a model room, instructors in civil engineering, plan drawing and writing, are much required but doctor Mowat will report on all these matters. We can never expect to have any but pupils of the humblest classes who much depend upon the daily labour for their daily bread; and the instruction they most require is that best calculated to fit them for the employment open to them.

Lt Col. W. H. Sleeman, Resident at Lucknow, 18 November 1852

An attitude of condescension and patronage, keeping in mind the demographics of the Institution, is exuded through remarks like these.

The first Principal of the College, John Newmarch had the unenviable task of collecting facilities for the new school. This was under constant scrutiny from a Local Committee that wished to have a say in everything. The selection of books, apparatus, teaching aids, living accommodation, etc. were all reported on almost daily, by means of Circulars. The angst is unmistakable, causing Newmarch to explode: “I earnestly request dispatch in this business as the College is not merely at a stand still, but the students are getting into bad habits for want of the means of affording instruction to them: in fact if it were not that it would bear the appearance of a wish to shirk work, I should recommend to the Committee to dismiss the scholars altogether until we are in a position to afford them effective instruction.” This radical suggestion led to series of power struggles; the British Resident Mr Davidson, refusing to attend the meetings of the Committee and the Principal refusing to attend on him in the Residency premises.

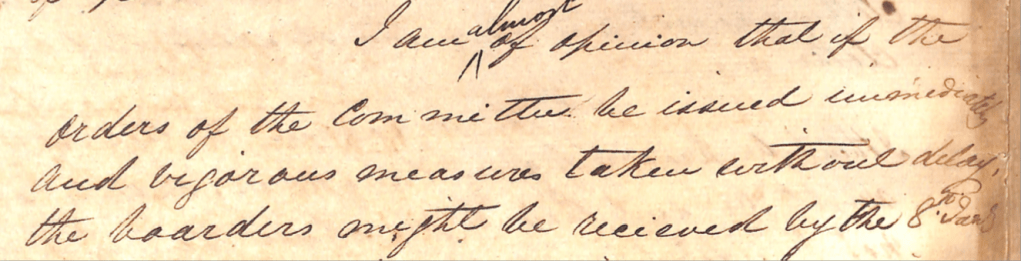

Principal, John Newmarch resigned his appointment on 31 September, 1846 after a tumultuous year. He was succeeded by Mr Leonidas Clint who took charge on 1 December, 1846. His immediate task was to make preparation for the reception of the resident Foundation pupils and Boarders. He was convinced that Boarders could be received by 8 January, 1847, if “vigorous measures taken without delay” were carried out.

Purchases of furniture and articles “indispensable to obtain before receiving the boys” were to be made from Cawnpore, while “the cooking utensils (could) be purchased in Lucknow, this may be said with certainty of those required for the Hindoos and Mahomedans.” By the end of January, 1847, Principal Clint was confident of establishing the Boarding House. He wrote: “I am of the opinion that I should be authorized to intimate to the parents or guardians of the Foundation scholars that the Institution is now open for the reception of this description of Boarders.”

Caste was an issue from the first days of the school. In the first year of the school’s existence, instructions had to be taken on the sensitive issue of caste Shortly after the opening of the school, a Circular dated 2 June, 1846 sought clarification:

“I should also bring to the notice of the Committee that an application has been duly and formally made by a boy of the Mihtur (Mehtar) caste for admission as a day scholar. It is much to be feared that this admission would tend to drive other boys from the College, but as there is no other objection to the admission of the applicant, the Principal cannot in the face of the decree which establishes the College take upon himself the responsibility of refusing his application. It appears to him a choice between injustice and inexpediency and he has requested that the advice and the directives of the Committee may be given him in the difficulty.”

Discrimination in admission on the basis of caste raised its ugly head again in 1849. Principal Clint sought special instructions from the Committee of Governors in this regard:

… 2. A boy of the Chumar caste has applied for admission. This not being an ordinary case, I solicit your instructions as to its disposal.

Circular No 157, 27 November, 1849

The response of the Committee was ambivalent. The British Resident of the time, the famous William Sleeman who ten years previously had supressed Thugee in North India, wrote in response to the Principal’s request for advice:

“I do not recollect what was determined by the Committee about the offer for. His claim to admission in the foundation was I think rejected and he proposes only to send another as a pupil on condition that the first was to be admitted.

“I know not whether the Rules admit of a Chumar being taken as a pupil – if not they should be adhered to – I think there are objections to it.”

Circular No 157, 27 November, 1849

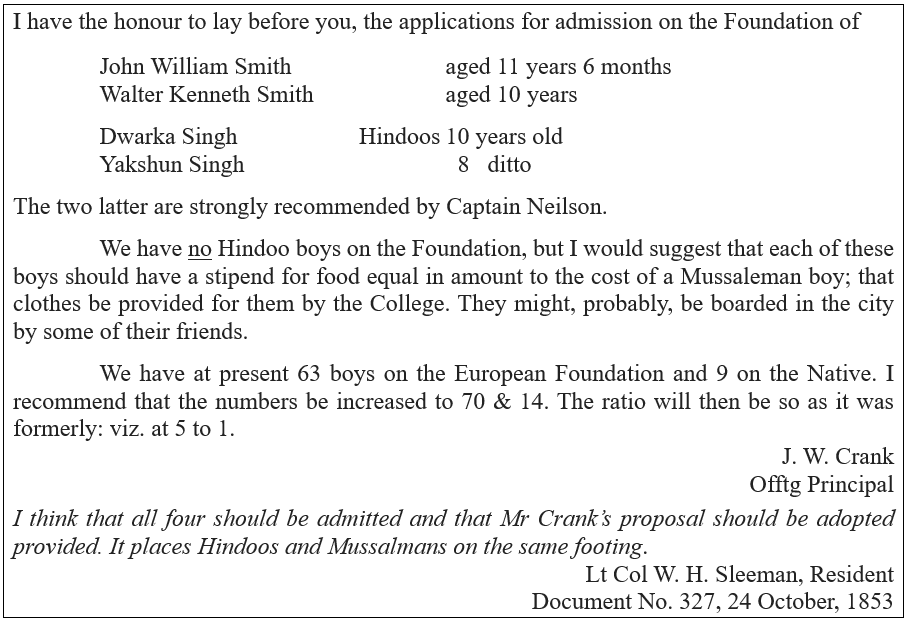

The mixing of communities in common living conditions took its own time. In 1853 it was recorded “We have at present 63 boys on the European Foundation and 9 on the Native. I recommend that the numbers be increased to 70 & 14. The ratio will then be so as it was formerly: viz. at 5 to 1.” The balance was heavily tilted in favour of the European Foundation. On the Native Foundation, Mussalman boys were entered early.

The first Hindu boys were admitted to the Foundation in 1853.

The admission of the first Hindu boys was recorded and shared with the Governors:

Seven weeks later, on 13 December, 1853, vide Circular No. 331 Mr Crank, officiating as Principal, in place of Mr George Schilling, recorded for the Local Committee of Governors:

Gentlemen,

I have the honour to forward for your inspection, lists of applicants for admission on the Foundation.

The European cases appear to be deserving of your notice, and I believe many of the native ones are also; most particularly: (Nos. 1, 2, 3, 4, 19, 23, 30, 35) to which I more particularly beg to draw your attention.

We have 16 vacancies for Europeans and 10 for Hindoos; the Mussalmans, already numbering ten.

The first attempts to attract paying resident scholars, a component of the Scheme of Administration, was unsuccessful. This is determined by inference following a Circular to the Committee, on March 25th 1856. Principal George Schilling acknowledged that Boarding pupils had not been attracted by the reasonable terms offered and determined a plan of making admission to the College desirable by the proposal of ‘Exhibitions’. These were traditional financial grants offered on grounds of merit or demonstrable necessity. It was hoped that the revenue of the College would be thus increased as well as attracting academically capable students.

Gentlemen,

I also beg to submit for your consideration, the following proposals:

1.

That the terms for boarders, be raised to 25 rupees per mensem, to include all charges, but for books and clothes. The present terms of Rs 15 per month have failed to attract boarders to the College and in my opinion, tend very much to lower the estimation in which it is held.

2.

That 30 exhibitions of three grades be established in the College.

10 of the first grade in value Rs 200 per annum each.

10 of the second grade in value Rs 150 per annum each.

10 of the third grade in value Rs 100 rupees per annum each.

They might be awarded either as scholarships for proficiency in knowledge as exhibitions to aid the boys of promising abilities, or as an assistance to those in needy circumstances towards educating their children. It appears to me that the following advantages will probably accrue from their establishment:

They will afford means of dealing with all applications for admission to the benefit of the Charity. According to the circumstances (more or less needy) of the applicants, they are likely to attract to the College a higher class of boys to the great advantage of those already in it and will increase its number without adding materially to the expenses of the Institution.

As the expense to the College of boarding a boy is considerably less than Rs 150 per annum, it follows that the holder of an exhibition of the First Grade will cost to the College 50 rupees per annum; of the Second Grade will cost the College nothing; of the Third Grade will pay the College 50 rupees per annum, so that it will be unnecessary to propose any reduction of the number of boys on the Foundation to provide funds for the establishment of these Exhibitions. That the course of instruction, the rules regarding the proposal, exhibitions and the arrangements of the College generally, be printed in the form of a Circular. That an abstract from the Circular be advertised in the papers with the dates on which the Committee will elect candidates, its admission to the Foundation as well as for exhibitions.

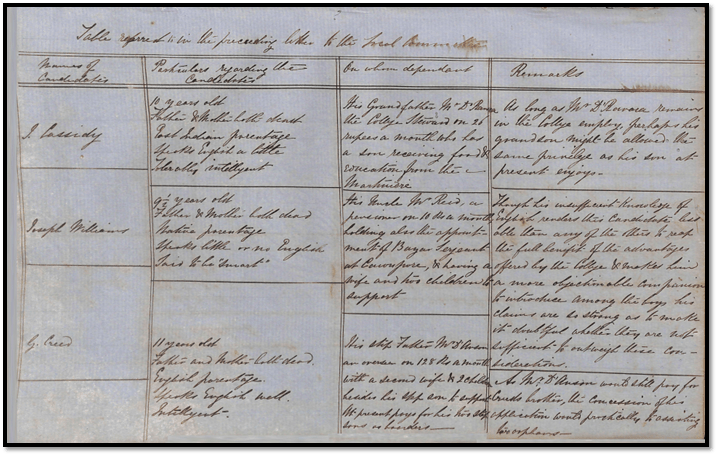

Charity came at a price, often at the arbitrary discretion of the Principal of the day. There is no evidence of a single application for admission to the Foundation, once recommended by the Principal, being turned down by the Committee. The ‘Descriptive Rolls’ prepared were personal and invasive. The documents provide an insight into the demographics of the boys who was admitted to the College. A sample from 28 April, 1857 is typical. It describes the circumstances of three applicants: J. Cassidy, Joseph Williams & G. Creed.

A cursory examination of the observations indicate the age of the boys (10, 9.5, 11), their Parents (all three orphans); Lineage (East Indian, Native, European); Knowledge of English (Little, little or no English, speaks English well) and on whom the boys were dependent. The Principal’s remarks were of significance: While Cassidy could be admitted his grandfather was in employed by the College; Joseph Williams’ lack of knowledge of English made him “a more objectionable companion to introduce among the boys”, while Creed’s candidature “wants practically to assisting two orphans.”

Leave a comment